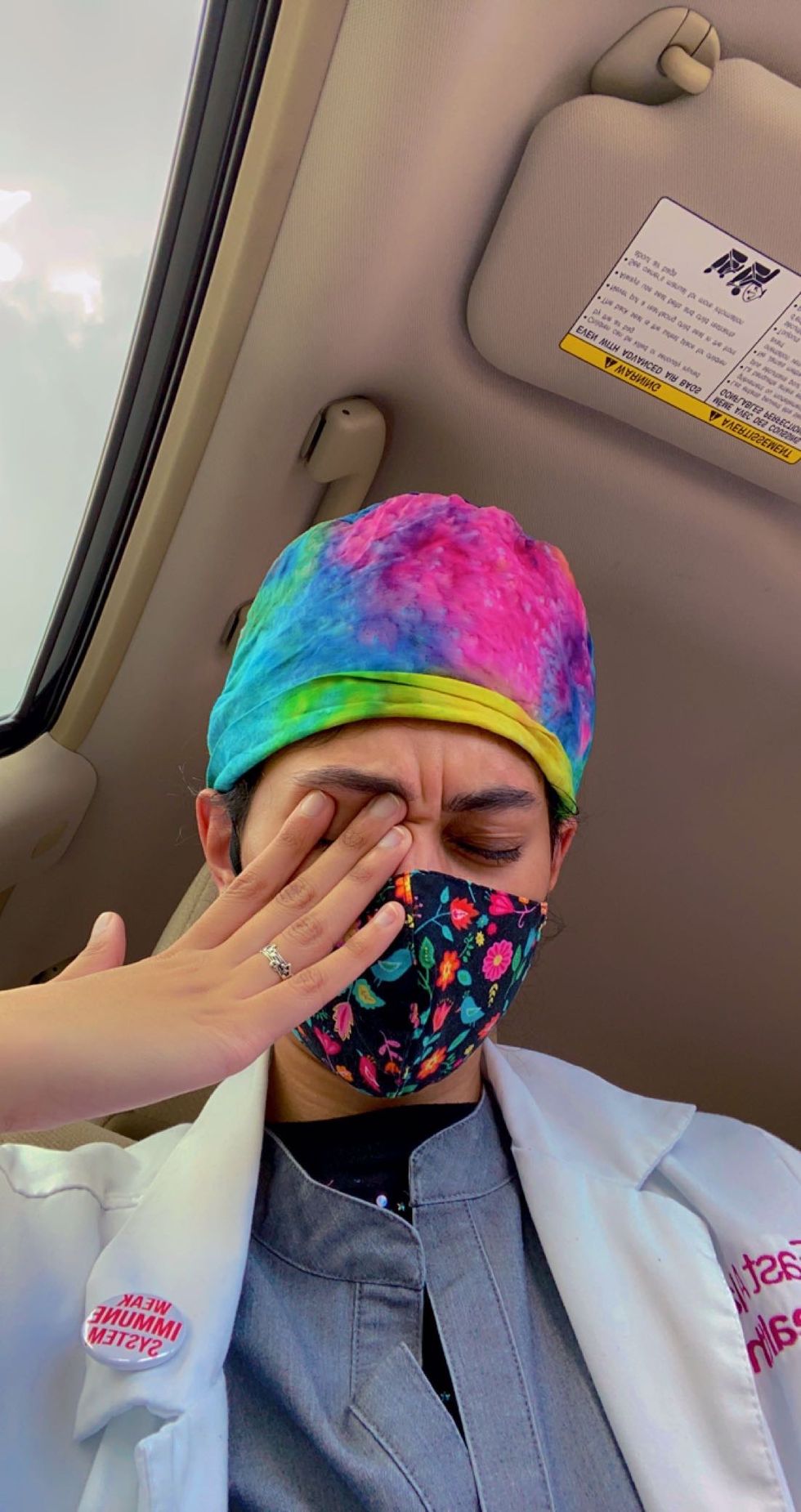

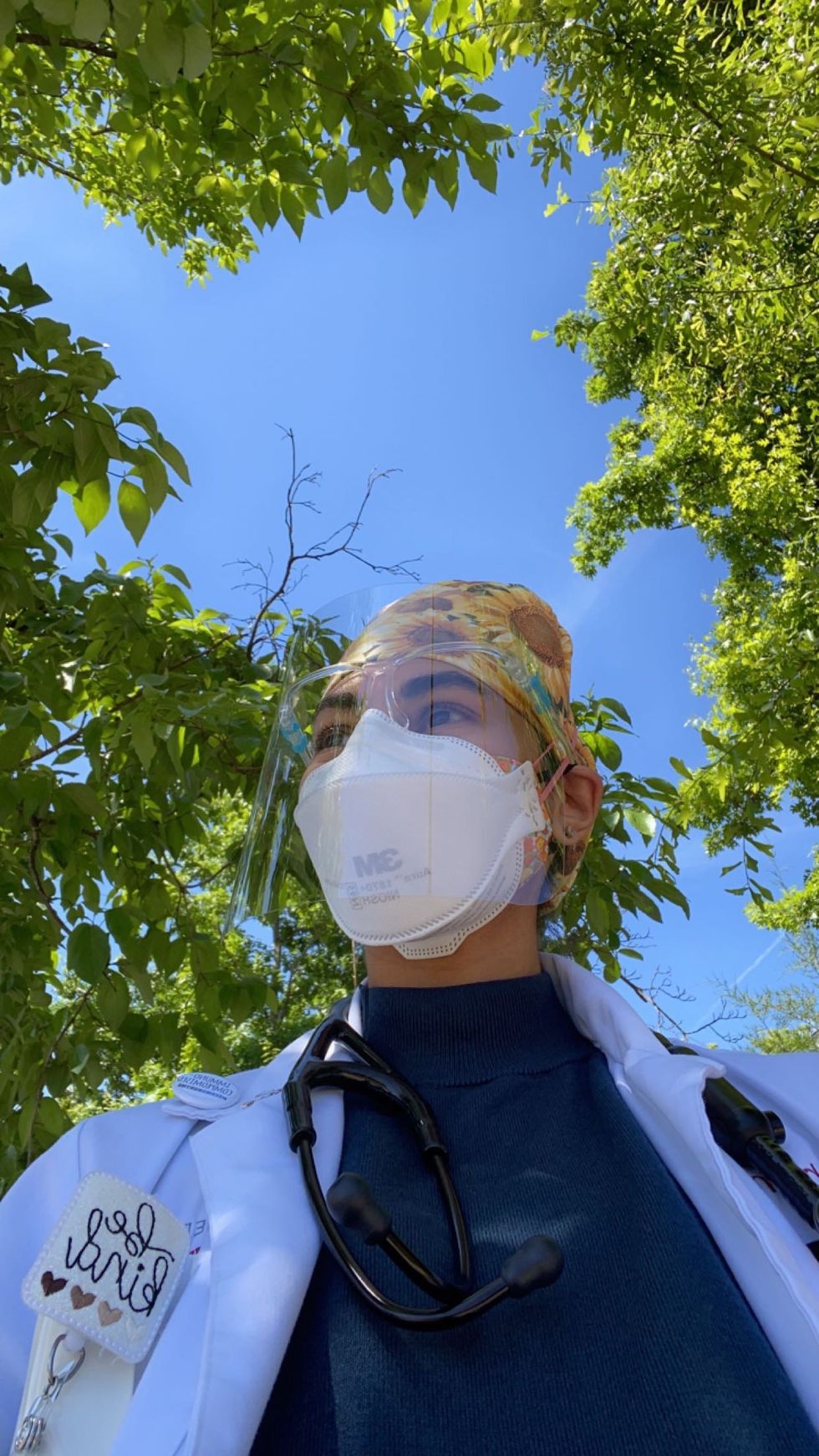

I got my first COVID infection in January 2020, before most people even realized the coronavirus was here. I was a third-year medical student, and I saw a patient who had just returned from Japan. In retrospect, he was really sick with very typical COVID symptoms—cough, fever, shortness of breath. I wasn’t wearing a mask when I saw him.

Within two days, I got really sick. My doctor had no idea what I was dealing with. (I wouldn’t find out I had COVID until May of that year when a blood test detected COVID antibodies in my body.)

During my clinical rotation in general surgery in February 2020, I started passing out from standing for long periods in the operating room. I didn't think anything of it at the time, but I kept getting worse. That was the first sign of postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (also referred to as POTS)—a diagnosis that would soon change my life.

More From Women's Health

I talked to so many doctors trying to find answers. They all blamed anxiety.

After feeling dismissed by doctors who chalked my symptoms and experience up to mental health issues, I decided to do research on my own. That's when I started seeing other people's stories about what many people call "long COVID" (when symptoms or side effects continue long after someone tests positive for the virus) and POTS online, and I thought, Oh my gosh, that must be what I have!

I was also losing all my hair, which research found is way more common with long COVID than previously thought. I also had chronic fatigue—I would get tired from taking a shower or getting up—severe joint pain, unusual rashes, and nerve pain in my hands and legs, all common long COVID symptoms.

I ended up contracting COVID a total of three times as the months rolled on and, each time, these problems were exacerbated.

All the cardiology tests I did were normal other than the sinus tachycardia, which is a faster-than-normal heart rhythm, a common symptom of POTS. But the cardiologists I saw initially were not willing to say that's what I had.

After seeing more than 15 physicians that year, I finally found a cardiologist who was a little bit more open.

They performed a modified table tilt test—which shows how different body positions affect your heart rate, heart rhythm, and blood pressure and is the gold standard for diagnosing POTS. The changes in my heart rate and blood pressure, as well as my other symptoms, all matched the diagnostic criteria for POTS.

I finally got my answer in March 2021, almost a year after I first developed symptoms.

For people with POTS, their blood vessels don't contract properly to promote blood flow to their heart and brain while they're standing. This causes dizziness, fainting, and exhaustion when standing for a long time.

So, the longer they're upright, the more their blood pools in the lower part of their body. This results in not enough blood returning to the brain and causes lightheadedness, brain fog, and fatigue. As their nervous system continues to pump out hormones to get the blood vessels to tighten, their heart rate increases, leading to chest pain and shakiness.

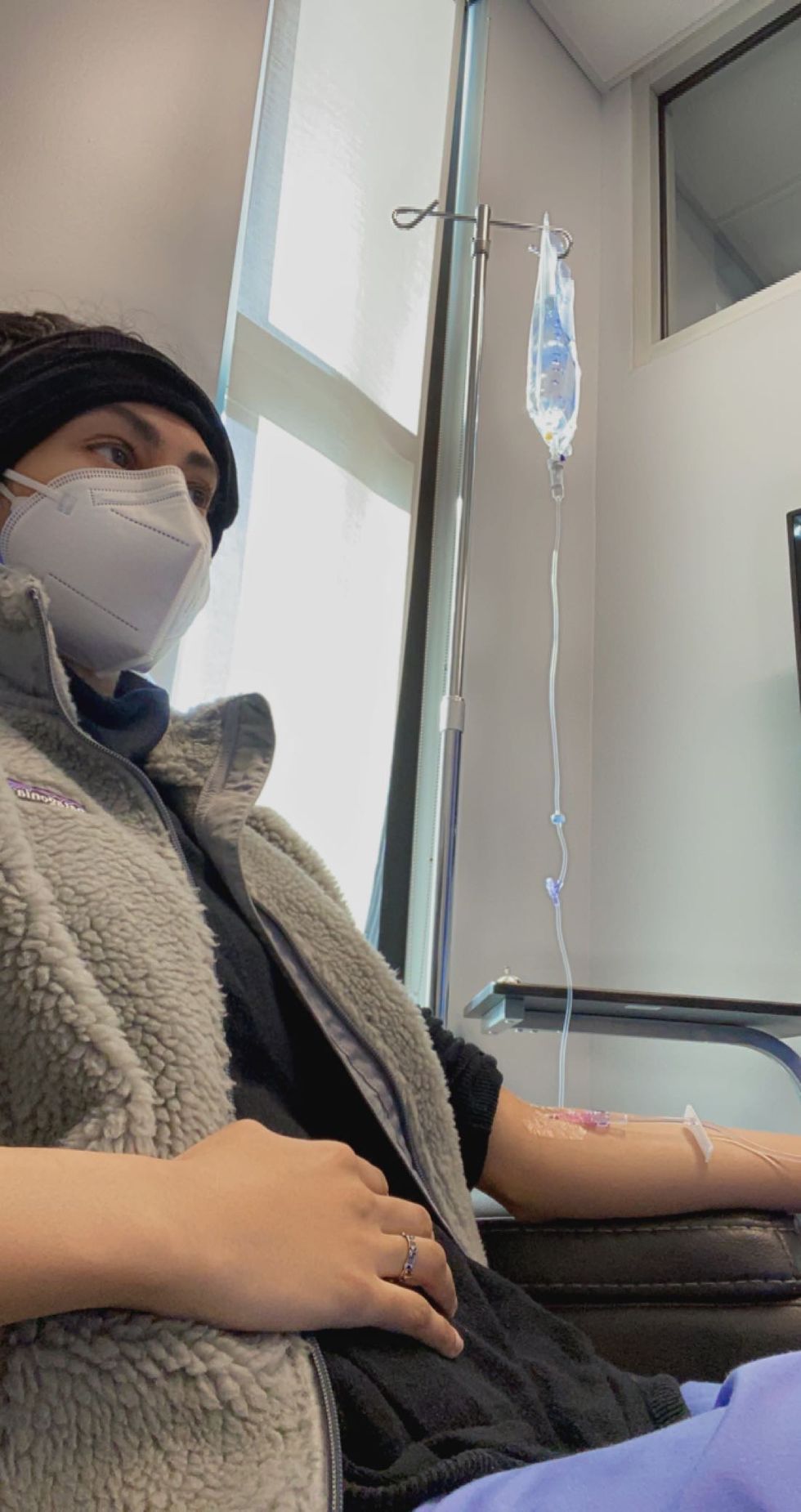

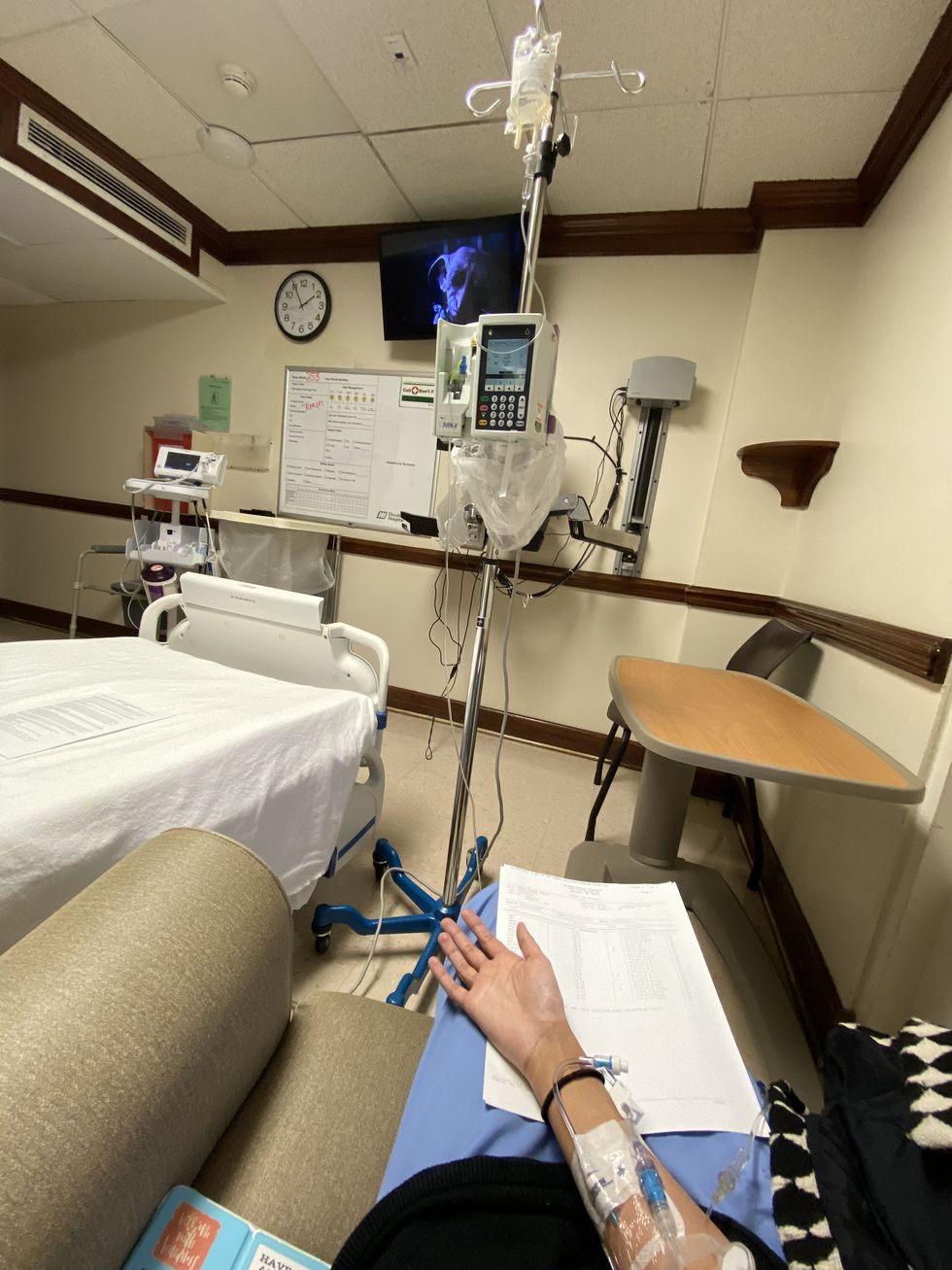

The treatment for POTS is mainly increasing blood volume to improve circulation. I started trying different medications, and none of them worked for me. So, I'm treating it by drinking a ton of water, taking salt tablets to help my body retain fluids, and wearing compression stocking to get my blood flow going. I also get a weekly IV infusion now of one to two liters of fluids depending on how sick I am.

I also received a long COVID diagnosis around that same time.

My persistent, lingering symptoms after getting my second infection finally convinced my doctor that’s what I have.

POTS diagnoses have become more common with long COVID, says Tae Chung, MD, an assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation and neurology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and director of the Johns Hopkins POTS Program. “Long COVID patients are presenting with fatigue, brain fog, a lot of GI symptoms, and exercising intolerance," he says. "Those look very similar to typical symptoms of POTS.” Up to 61 percent of survivors may develop POTS-like symptoms after a severe COVID infection, according to a recent study.

It's not completely clear yet why some people with long COVID develop POTS. One theory is that the virus stays in the body, says Dr. Chung, and POTS is the result of chronic low-grade inflammation, which has been linked to other long COVID symptoms such as brain fog in a recent study.

Not everyone who gets COVID will develop POTS. I may have been predisposed because of a genetic condition.

I had a lot of GI issues growing up, which got a lot worse when I hit puberty. I also had immune system problems throughout high school and college, and I went blind in my left eye temporarily at one point. When I first learned about a connective tissue disorder called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) in college, I realized that probably explains all these health problems I've had. I didn’t want to believe I have it, so I never got tested.

The severe complications from my third COVID infection made me decide to find out if I could also have EDS. In May 2022, a dermatologist, rheumatologist, and genetic counselor confirmed that I fit all the criteria for EDS.

The inflammation and damage from COVID seemed to have made my fragile connective tissue even weaker. I was having more dislocations of my shoulders, hips, and knees. I also learned that this disease likely predisposed me to POTS. A lot more people should get screened for EDS because they may have POTS as a result of this but have no idea.

A lot of POTS patients, whether they develop it due to COVID or not, are predominantly young women in their 20s and 30s, and many of them have Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, says Dr. Chung. “We don’t know the relationship between EDS and POTS at this point, but people with EDS may be more genetically predisposed to POTS,” he adds.

My biggest health takeaway: You have to be your own advocate.

A lot of doctors won’t take you seriously, especially if you’re a woman. They may say that this is all psychosomatic. But we as patients know our bodies best.

When someone tells you something that doesn't align with how you're feeling, know that you can go to another doctor. If you know something is wrong, just keep at it and don't take no for an answer. I had to persist with a lot of doctors and it took me a year, but I got there—and so can you.