As a biracial child, Sarah* felt her appearance was constantly scrutinized by the Filipino side of her family. And when she hit puberty and started to develop curves, the body talk escalated.

“I wasn’t overweight, but my family, the Filipino side, really started making comments about my weight to the point where my self-esteem really started to suffer,” she says. “I lost so much confidence because of it.”

She still remembers a comment an uncle made when she was in eighth grade and one of the star players on her school’s basketball team: “How can she play basketball if she’s so fat?”

The Philippines was colonized by Spain in the 16th century and later occupied by the United States from 1898 to 1946. Today, Filipino beauty ideals are still Western-emulating and prize thinness, fair skin, and European features like a sharper nose, says Leilani Salvo Crane, PsyD, a psychologist in New York whose practice focuses on serving the BIPOC community, especially individuals of Asian descent. She also has particular expertise in the treatment of eating disorders.

And in Filipino families, comments about everything from someone’s skin tone, eyes, and weight to their education are fair game. “There is no holding back. There is no filter,” says Crane. “As an elder, you can say whatever you want. And as a younger person, you just have to take it—preferably with a smile.”

It’s considered disrespectful to talk back to elders. “Body shaming was part of the culture,” Sarah says. “I tried to shake it off and tune it out.”

When Sarah was in high school, her dad passed away after a long illness. To cope with her grief, she started to restrict her eating. After most meals, she’d throw up.

“I couldn’t control my dad dying. I couldn’t control the fact that I had the ACT coming up. But I could control how much I was eating,” says Sarah, who is now in her 30s.

Her mother noticed she was eating less but didn’t see her weight loss as a problem.

Decades later, Sarah thinks that not being a “stereotypically small Asian girl” impacted her care—and allowed her eating disorder to go unnoticed.

Sarah remembers an assignment in science class that was supposed to illustrate how human metabolism worked. Her teachers asked that everyone keep a food diary and log their calories for a week. An honor student, Sarah told the truth: She consumed only 400 or 500 calories per day.

“I was in denial,” she recalls. “But I thought, If the teacher says something, that means there’s a problem. I wanted someone else to see the problem and acknowledge it.”

Instead, her homework came back with a note across the top: “You must have miscalculated.”

Eating disorders are more common in the AAPI community than many realize.

Among clinicians, there’s a misconception that eating disorders mainly affect white, upper-middle-class female patients, says Shuchang Kang, PhD, a staff psychologist at UCLA Counseling and Psychological Services who studies disordered eating in marginalized groups. But the rates of disordered eating behavior among Asian American women are comparable to rates seen among white women, according to a 2019 study from the University of Nevada at Las Vegas.

Asian Americans also had higher disordered eating rates compared with other women of color, finds a 2019 study from the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. Another 2018 study published in Eating Behaviors found a slightly higher rate among Asian Americans (21.5 percent) compared with whites (19.8 percent), Hispanic Americans (19.9 percent), and African Americans (20.7 percent).

Clinicians are less likely to diagnose people of color with an eating disorder, even if they show symptoms, says Kang. They struggle to identify eating disorders in Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) patients for several reasons, including those due to stereotypical assumptions (as in, Asians are tiny, thin, size 00), says Crane. And Asian Americans are less likely to seek out mental health care in general, so numbers are naturally lower. As a group, AAPIs have the lowest help-seeking rate of any racial or ethnic group, with only 23 percent of adults with a mental illness receiving treatment in 2019, according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness.

Also, due to intrinsic bias, healthcare professionals may fail to ask questions during the intake process to reveal an eating disorder. This may be partially due to the societal view of Asian Americans as the “model minority.” The model minority myth lumps all Asians into one monolithic group and stereotypes them as obedient achievers who reach a higher level of success than other minorities. “It’s a racial wedge,” says Crane. “It’s meant to create resentment among ethnic groups.”

And patients themselves may not recognize that they have an eating problem, either, notes Crane. “There are some times when I don’t catch it,” she says. “Either someone doesn’t want to tell me, or that’s not the presenting problem.”

Societal and cultural expectations are often at the root of disordered eating among Asian Americans.

Societal expectations extend beyond the West. There is a collective pressure to maintain thinness as a standard of beauty in Asian countries. Japan, for instance, established a national limit on waistlines in 2008. In South Korea, values may emphasize appearance as more important than ability or talent in determining a woman's success in marriage or career. Billboards in the country also promote diuretics to lose weight, Crane adds.

While Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders are often grouped together, says Crane, in traditional Fijian culture, a stronger, heavier body type is the beauty ideal for women. But in the late ’90s, the previously isolated islands began broadcasting Western television and media, per a 2015 review of studies in the Journal of Eating Disorders. After three years of exposure to Western television, researchers found that ethnic Fijian girls had a significant increase in two indicators of disordered eating: purging and high scores on the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26), which is used by clinicians to identify the presence of eating disorder risk, finds 2018 study in The British Journal of Psychiatry.

When it comes to expectations about body types, some white people also believe that Asians as a group are “naturally” thin. Alison, who is in her 30s, was adopted from South Korea by a family in the United States when she was a baby. She says she developed disordered eating behaviors at a young age. Her mother weighed her daily, taught her to count calories, and grounded her if she gained weight. Although she wasn’t raised in an Asian culture, Alison believes the standard of beauty for Asians played a role in her mother’s perception of her body.

“My mother kept saying things like, ‘You know, if you truly were at the right weight, you wouldn’t have boobs, and you wouldn’t have curves.’ Or, ‘You don't understand how delicate your bone structure is,’” she recalls.

Alison thinks her mother assumed that she should be as thin as the Asians who appeared in the media, even though she has always been curvy. She was 26 when she sought help by attending an Overeaters Anonymous support group for a year. Nine years later, Alison is still recovering from disordered eating and believes she always will be.

“Very well-meaning parents can still have some internalized racism when raising a child that is different from them,” she says.

‘The pressure to be perfect is unbelievable.’

Mindy*, a Taiwanese American who works in the entertainment industry, grew up in a household that valued thinness but also loved food. She was always applauded for being able to eat a lot and stay skinny. But her family’s comments made her self-conscious. She recalls her mom constantly saying that she was jealous of her metabolism—and then casually deriding other people for being “chunky” in the next breath. “I knew if I were to gain weight, my value would diminish,” she says.

Mindy was around 5 years old when she began demonstrating disordered eating behaviors. She overate to compensate for feelings of inadequacy. “I needed to eat to feel happy and loved,” she says. “In my head, I never had enough food. But really, I never had enough attention or security.”

Mindy’s parents also praised her for her singing and acting abilities—and her looks.

“I wanted my family to love me, and I wanted them to be proud of me,” she says. “So I ate everything. Even when I didn’t want to, even when I wasn’t hungry.”

The desire to be perfect is a common contributing factor among eating disorder patients in the Asian American community, Kang says. Therapists who worked with Asian Americans reported that their clients with eating disorders felt the need to live up to their parents’ academic, professional, and appearance-based expectations, finds one 2015 study from California State University at Fullerton.

“That pressure to be perfect, I hear that repeatedly in my patients of Asian descent who struggle with eating disorders,” Crane says. “The pressure is unbelievable.”

Eating disorders may manifest as a form of “silent protest,” Crane adds. “You’re not verbally saying anything, but your body is speaking volumes.”

“Imagine that you’re trying to be a good girl and please your parents,” she says. “But you have frustrations, pressures, and things you can’t talk to your parents about because they will just push back or tell you to suck it up. Eating disorder behaviors can be the only thing you can do under the thumb of your parents. And you’ll likely be praised for the result.”

The desire to be “perfect” can get in the way of getting help.

During grade school and high school, Mindy’s eating issues mostly faded and were replaced with anxiety about fitting in and dating. When she attended a liberal arts college where the female form was celebrated, she felt free. For the first time, she was unafraid of gaining weight.

After graduation, she pursued an acting career. She landed her first big role playing a ballet dancer and was told to lose weight. And even though she exercised and worked with a nutritionist, she still felt the residual effects of her disordered eating as a child. “I still didn’t know how to deal with my emotions,” she recalls. “So all the good, all the bad was still getting taken out on food.”

For seven years, she yo-yoed between gaining weight and then crash dieting to lose it again.

But she dealt with a lot of shame before she sought out a therapist. She remembers logging on to the National Eating Disorders Association website and seeing actress Jamie-Lynn Sigler from The Sopranos as their celebrity ambassador and thinking to herself, Oh, I could never do that. It would be just so humiliating having everyone know I was struggling with food. Mindy worried that being open about her eating disorder would hurt her job prospects.

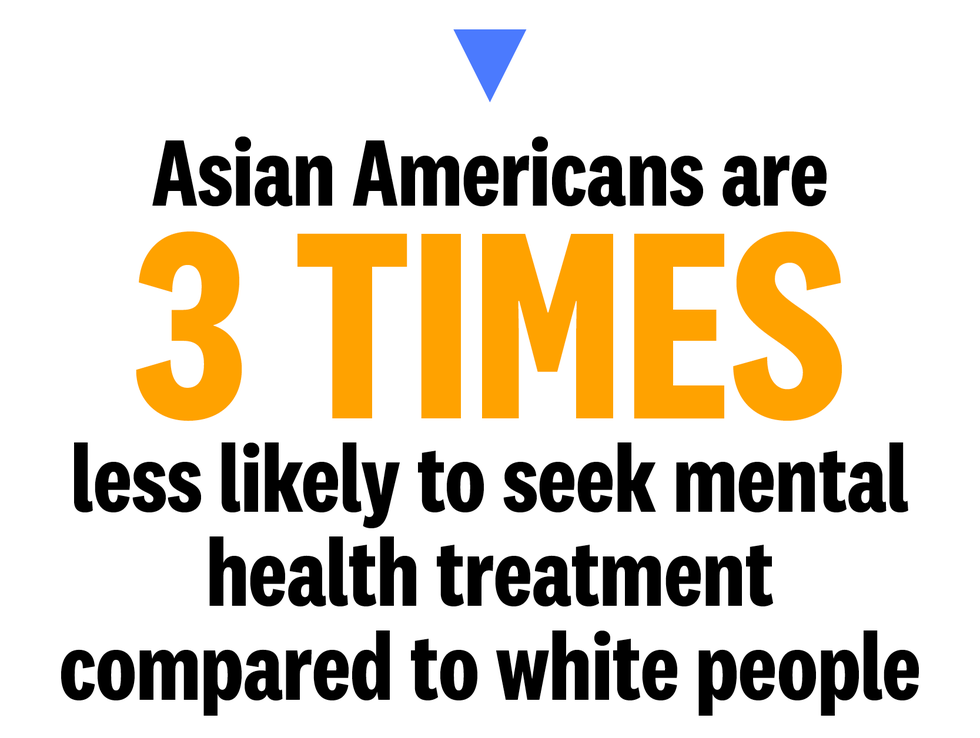

When it comes to seeking professional help, there are multiple barriers to entry. Asian Americans are three times less likely to seek mental health treatment compared with white people, according to the American Psychological Association. Part of that is due to the stigma attached to seeking mental health services in the Asian American community. “It’s much more acceptable in pan-Asian culture to go to a doctor for a physical ailment than for anything emotional,” says Crane. She points to Korea as an example, where the only mental health treatment available in that country is inpatient care: “Basically, you’re put away and you’re never heard from again.”

There are also socioeconomic and class considerations. Many of Crane’s patients had to act as translators for their parents starting at a young age. “What if your parents speak no English and you’ve had to take care of filling out paperwork for them, or phone calls? What if there is very little money?”

Sometimes, it’s not shame that keeps someone from seeking help. People might not recognize that they even have an eating disorder. A recent patient came to Crane looking for help managing her anxiety and depression. But as they started working together, Crane realized her patient also had a significant eating disorder that she didn’t think was a problem. In her mind, she was doing what was needed to maintain a standard of beauty.

Reframing your thinking can help heal your relationship with your body—and your family.

Experts say there are several things you can do to stay mentally strong amidst cultural expectations over body size and shape. Crane and Kang offer the following tips:

- If you have an older relative you can confide in, ask if they can talk privately to the person who’s been shaming you about not commenting on people’s bodies.

- If you can’t talk to your family about your eating or body issues and aren’t able to see a therapist, talk to friends or allies about it.

- During family gatherings or holidays, have a buddy system in place. Remember that you can always leave a situation. Plan your exit, like going on a walk with a cousin or friend. Have someone you can text or call during the event.

- Seek out a culturally sensitive therapist who can help you work toward body neutrality and coping with negative comments.

- Keep in mind that if you suspect that a loved one has an eating disorder, they often will deny it at first and may not want to seek treatment.

For Sarah, the most valuable part of her healing journey was connecting with other Filipino women who have also experienced eating disorders and are committed to not body-shaming the next generation.

“I lost so much of my shameful feelings,” she says. “Someone in the group chat will say, ‘My mom yelled at me and called me fat.’ And then someone else will say, ‘I’ve been through the same thing.’”

A few years ago, Sarah’s aunt from the Philippines came to visit. “She gave me a really sad look, like, ‘Oh my god, look at your body,” she recalls. Sarah replied, “Yeah. I’m here. And I’m alive, and my body has gotten me through that. So, thank you.”

*Names have been changed

How to Find Culturally Relevant Care

Seeking care from mental health professionals who are responsive to an individual’s culture is essential in any type of mental health treatment, including when it comes to eating problems, says Crane.

For Asian Americans, she suggests the following resources: